Why Girls have been harder to diagnose with ADHD!

According to the Swedish ADHD-Center in Stockholm, early research on ADHD was mainly focused on boys and men because the pervading thought among professionals and researchers was that girls could not have ADHD!

https://docplayer.se/4325867-Flickor-med-adhd-anna-hogfeldt-leg-psykolog-adhd-center-2013-08-22.html

Girls with ADHD have been noted to have significantly lower self-esteem compared to their peers and are at risk for alarming behaviors such as cutting/hurting themselves and suicide especially when they enter adolescence and become young adults!

Because of these risks, it’s extremely important that more resources and focus are directed towards correctly diagnosing girls at an early age.

Annie Eklöv (Source https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2012/08/girls-adhd)

Hippocrates often called the father of modern medicine, described some patients who had ADHD symptoms

The earliest mention of what seems to be ADHD was by Hippocrates (460-375 BC). He lived in Greece and made one reference to some patients who had trouble focusing on anything specific and were extremely quick to react to stimuli in their vicinity.

Hippocrates thought that Earth, Water, Air, and Fire corresponded to the functions of the body and needed to in the right balance. His suggested treatment for these ADHD-like symptoms was a restricted diet, lots of water, and plenty of physical exercises!

That honestly doesn’t sound like bad advice!

Annie

(Sources) https://mentora.gr/hippocrates-the-elements-of-nature-in-the-human-body/ https://chadd.org/adhd-weekly/more-fire-than-water-a-short-history-of-adhd/

Sir Alexander Crichton Described ADHD Symptoms in 1798

In 1798 Sir Alexander Crichton describes ADHD or what appears to be a similar disorder. Crichton was born in 1763 in Edinburgh and became a Scottish physician.

Soon after becoming a physician, he decided to practice medicine in different cities throughout Europe. It was during this trip he became increasingly interested in mental illness. Crichton observed and wrote about many cases of insanity and mental illness both in males and females. (Source) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3000907/#CR20

”In this disease of attention, if it can with propriety be called so, every impression seems to agitate the person, and gives him or her an unnatural degree of mental restlessness.”

Crichton A (1798) An inquiry into the nature and origin of mental derangement:

Heinrich Hoffmann Described Children with Symptoms Similar to ADHD in 1844

A German physician created some illustrated children’s stories in 1844 which describe the difficulties of what seems to be ADHD. His name was Heinrich Hoffmann. Some of his characters were “Fidgety Phil” and ”Johnny Look-in-the-air”.

These characters were most likely based on children he met in his medical practice. Even though there was no official diagnosis called ADHD at the time, he observed the difficulties these boys were having, which happened to be very similar to ADHD.

Symptoms were historically easier to detect in boys.

Sir George Frederic Still’s lectures, in 1902, are considered by many to be the Beginning of ADHD’s Scientific History

In the Goulstonian Lectures which Sir George Frederic Still gave in 1902, he scientifically addressed the symptoms of ADHD. He was the first to do so and Still, could be considered the Father of the Scientific History of ADHD.

Many authors on the subject of ADHD choose to begin their History of ADHD with Still’s lectures because they conclude that this is the scientific starting point for ADHD.

Sir George Frederic Still was born in Highbury, London, in 1868. He became a pediatrician and researched childhood disease. He is most famous for his research on the chronic joint disease in children which became known as Still’s disease.

Still presented his observations of children in his Goulstonian Lectures, “On Some Abnormal Psychical Conditions in Children” (Still 1902). He observed worrying behavior in children which he called ”Abnormal defect of moral control”. He went on to define moral control as ”The control of action in conformity with the idea of the good of all.”

(Still 1902, p. 1008)

He observed that children who were mentally retarded had no moral control, but he also observed another group of children who had poor moral control whom he thought warranted careful observation. His descriptions of these cases are now considered to be historical descriptions of ADHD. He noted that these children had no “general impairment of intellect” (Still 1902, p. 1077).

Still observed 5 girls and 15 boys in his study of the “defect of moral control as a morbid manifestation, without general impairment of intellect and without physical disease” (Still 1902, p. 1079).

He did not look at this disproportionate ratio as accidental, and it reflects the ratio of boys and girls who are diagnosed with ADHD even today.

”The ratios of DSM-IV-like inattentive and combined type ADHD prevalences in males versus females fell approximately between 2:1 and 3:1 and were highest in adolescents. For the predominantly hyperactive-impulsive subtype, the male: female ratio was about 2:1 in children, but was lower in adolescents and adults.” (Source, * www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ see footnotes)

In my opinion, this ratio does not fully reflect the number of girls who live with ADHD. My daughter was older than my son when she was diagnosed because she hid her symptoms well.

If she didn’t understand what the teacher asked the class to do she observed what her friends were doing and copied their behavior.

It wasn’t until her teacher caught her doodling on her homework several times that they realized she had a problem with attention. She was later diagnoses with ADHD inattentive (ADD).

Annie Eklöv

Still found that the children he studied struggled to delay gratification as well as having “a quite abnormal incapacity for sustained attention. Both parents and school teachers have specially noted this feature in some of my cases as something unusual” (Still 1902, p. 1166).

Some of the finding in his research are still used as criteria for recieving an ADHD diagnosis today!

Tredgold (1908) Postencephalitic behavior disorder

We have the Postencephalitic behavior disorder to thank for sparking interest in research into symptoms and behaviors which had many similarities to ADHD.

Tredgold was only one of many authors who wrote about postencephalitic behavior disorder. These men wrote about the encephalitis lethargica epidemic (1917-1928) and observed the symptoms that altered the personalities of those who managed to survive. (Conners 2002 [CrossRef])

20 million people are thought to be affected by the encephalitis lethargica epidemic, and cases of similar symptoms although rare are still observed today.

It affects men and women and is thought to be linked to ”Autoimmunity against deep grey matter neurons.”

( source https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14570817/)

Tredgold and his colleagues were observing the effects of early brain damage and linking this to learning difficulties.

Not all of the children which these men observed would meet the criteria for an ADHD diagnosis today, but their conclusions sparked an interest in studying Hyperactivity in children, and it fueled further scientific studies which helped develop the idea of a condition called ADHD.

Franz Kramer and Hans Pollnow Observed the Hyperkinetic Disease of Infancy in 1932

The German Physicians Franz Kramer 1878–1967, and Hans Pollnow 1902–1943 were both Jews working under Karl Bonhoeffer at the psychiatric and neurological hospital at Berlin’s Charité. When Hitler rose to power, they were both forced to emigrate, and little is known about their later work.

They observed infants exhibiting behaviors that are very similar to modern ADHD behaviors. These infants were continually plagued by ”motor restlessness.”

(Kramer and Pollnow 1932, p. 1).

Kramer and Pollnow were first to distinguish these symptoms from other similar symptoms like postencephalitic behavior disorder and other disorders. They noted that they were not the first to observe this disorder (Hyperkinetic disease of infancy), but other authors did not distinguish these symptoms as its own disorder.

The children they observed were overactive and always seemed to be in motion. They acted on their impulses which often resulted in inappropriate physical activity for the situation they found themselves in.

The hyperkinetic disease causes children to fidget, engage in inappropriate physical activity, or touch, move, or play with objects in their vicinity although these behavior seem to have no purpose or goal.

(Paraphrassing, Kramer and Pollnow 1932, p. 7, p. 9)

They observed that even though these children did not play the same game for more than 5 minutes most days, they could at times, concentrated extensively on a task, game, or object much like the ‘Hyper Focus’ which ADHD kids are known for today.

Kramer and Pollnow noted that these children. . .

- Were easily angered

- They had unstable moods

- They often cried at small offenses or minor setbacks

- They were impulsive

- They were easily excitable

Because Karmer and Pollnow often refer to those they observed as children and not boys or girls we can assume that they were observing both boys and girls in their studies of the hyperkinetic disease of infancy.

In 1937, Charles Bradley Became the First to Find a Treatment for Hyperactivity

The Bradley Hospital, in East Providence, Rhode Island, was where Charles Bradly conducted his reasearch. During Bradly’s time it was called, Emma Pendleton Bradley Home. The ‘Home’ was founded by Bradly’s great-uncle George Bradley (Brown 1998) who opened the hospital to treat children with neurological impairments (Conners 2000).

The Hospital received children with a wide range of neurological problems some of which had problems with their emotions, learning difficulties, and behavioral problems which were similar to the criteria we have for an ADHD diagnosis today

(Gross 1995).

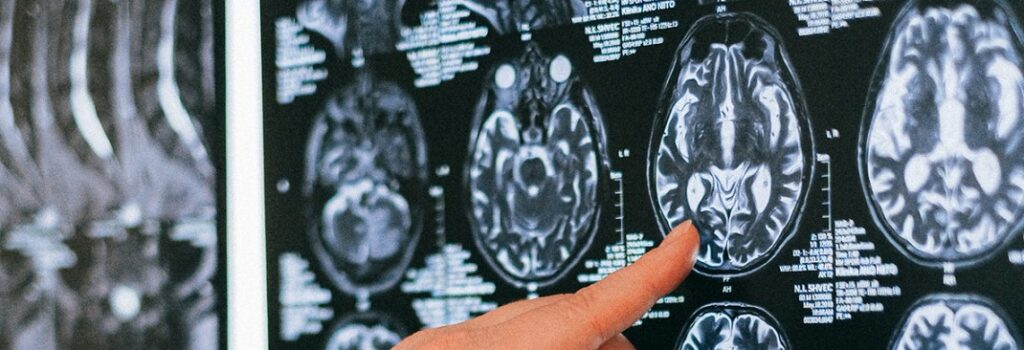

Bradly studied structural brain abnormalities (Rothenberger and Neumärker 2005) by performing pneumoencephalograms this caused migraine-like headaches which he tried to treat with benzedrine. Benzedrine was a stimulant used in 1937.

Although Benzedrine was not successful in treating headaches Bradly was surprised that roughly half of the children taking the stimulant suddenly began performing much better in school! He decided he needed a more systematic approach and started a trial with 30 kids.

“The most spectacular change in behavior brought about by the use of benzedrine was the remarkably improved school performance of approximately half the children”

(Bradley 1937, p. 582)

“It appears paradoxical that a drug known to be a stimulant should produce subdued behavior in half of the children. It should be borne in mind, however, that portions of the higher levels of the central nervous system have inhibition as their function, and that stimulation of these portions might indeed produce the clinical picture of reduced activity through increased voluntary control”

(Bradley 1937, p. 582)

Bradley eventually identified which children had the best chances of benefiting from Benzedrine.

These children had. . .

- Short attention spans

- Dyscalculia

- Mood lability

- Hyperactivity,

- Impulsiveness

- Poor memory”

[Source (Conners 2000)]

Even though Bradley’s findings were revolutionary it took years for other doctors and researchers to give him the recognition he deserved and take notice of the conclusions he made in his research.

Benzedrine became proved by the FDA in 1936, but it was not meant to improve children’s attention. It was approximately 25 years later that people became interested in Bradley’s research and began to see the possibilities of stimulant treatment.

Benzedrine is no longer in use.

Bradley treated ‘Children’ during his medical practice. I can not find specific information about the ratio of boys to girls that were treated at his hospital.

Leandro Panizzon Synthesized Methylphenidate in 1944

Methylphenidate or ”Ritalin” was first synthesized by Leandro Panizzon in 1944 and production began at the Ciba-Geigy Pharmaceutical Company in 1954. Ciba-Geigy marketed the drug as ”Ritalin.”

Fun Fact:

Ritalin was named after Panizzon’s wife Marguerite or ”Rita”.

(Rothenberger and Neumärker 2005).

Ritalin was first marketed for “a number of indications such as chronic fatigue, lethargy, depressive states, disturbed senile behavior, psychosis associated with depression and narcolepsy”

(Leonard et al. 2004, p. 151).

It wasn’t as effective in treating the above symptoms as it was in helping those with ADHD concentrate. Ritalin is still thought to be the most effective drug for ADHD and is the most frequently prescribed ADHD medication and is prescribed for both boys and girls. (Döpfner et al. 2000).

Mild Brain Damage as the Cause Hyperactivity was researched for many years 1930s-1960s

Research from the 1930s and 1940s supported the idea that abnormal behavior could be caused by brain damage. (Ross and Ross 1976).

Tredgold mentioned in his research that, infants could have mild brain damage which went unnoticed until the child started school. This was, in part, the basis for the new idea that slight brain damage can cause hyperactivity.

(Ross and Ross 1976).

They thought “that even when brain damage could not be demonstrated it could be presumed to be present” (Ross and Ross 1976, p. 16) which is a rather alarming assumption.

Laufer and others observed many children and I can not find any information on the ratio of boys to girls who were observed to support the idea of Mild Brain Damage causing hyperactivity.

Laufer went on to describe the characteristics of this ‘Syndrome’ and he could have been describing ADHD. Infact the symptoms are so similar that the concept of ‘Minimal Brain Damage’ is considered a historical antecedent to ADHD.

”It has long been recognized and accepted that a persistent disturbance of behavior of a characteristic kind may be noted after severe head injury, epidemic encephalitis and communicable disease encephalopathies, such as measles, in children.

It has often been observed that a behavior pattern of a similar nature may be found in children who present no clear-cut history of any of the classical causes mentioned.

This pattern will henceforth be referred to as hyperkinetic impulse disorder.

In brief summary, hyperactivity is the most striking item. This may be noted from early infancy on or not become prominent until five or six years of age.

There are also a short attention span and poor powers of concentration, which are particularly noticeable under school conditions. Variability also is frequent, with the child being described as quite unpredictable and with wide fluctuations in performance. The child is impulsive and does things “on the spur of the moment,” without apparent premeditation. Outstandingly also these children seem unable to tolerate any delay in gratification of their needs and demands. They are irritable and explosive, with low frustration tolerance.”

(Laufer et al. 1957)

In the 1960’s the idea of ‘Minimal Brain Damage’ was supplanted by the concept of ‘Minimal Brain Dysfunction’

The idea of Minimal Brain Damage was well established in the 1960s, but it became highly criticized as the tests, used to determine brain damage, came into question.

Laufer was dissatisfied as “children who present the hyperkinetic impulse disorder without having any of the classic etiologic traumatic or infectious factors in their historical backgrounds” could not be explained in the ‘Minimal Brain Damage’ theory.

(Laufer et al. 1957).

Laufer and his colleagues continued to study children with Hyperkinetic Syndrome they compared EEG from kids with Hyperkinetic Syndrome to EEG from kids without the Syndrome. They found that when they administered amphetamines, the EEG of the children with Hyperkinetic Syndrom was similar to children who did not have the syndrome.

They concluded that a dysfunction of the diencephalon could be the cause of the hyperkinetic syndrome (Laufer et al. 1957).

The Oxford International Study Group of Neurology thus decided that ‘Minimal Brain Dysfunction’ was better terminology than ‘Minimal Brain Damage’ (Ross and Ross 1976; Rothenberger and Neumärker 2005).

A concept evolved of three main symptoms which warranted a diagnosis ‘Minimal Brain Dysfunction’

- Inattention

- Impulsivity

- Hyperactivity

It was also agreed that children with ‘Minimal Brain Dysfunction’ had a normal range of intelligence when compared to children who did not have minimal brain dysfunction.

This was a major step forward from the idea that these children had brain damage and were somehow mentally subnormal. It was an important development for forming a complete picture of what would later be called ADHD.

(Conners 2000, p. 182) (Clements 1966, p. 9)

Historically ADHD was studied in ‘Children’ and the specifics of how many boys or girls were involved in a study can be hard to find. We can assume that most studies looked at more boys than girls because it was often easier to identify ADHD symptoms in boys.

The hyperkinetic reaction of childhood 1968

The idea of ‘Minimal Brain Dysfunction’ began to decline during the 1960s. Although the idea lived on till the1980s considerable doubt was cast on the concept. Minimal Brain Dysfunction was considered non-specific and researchers wondered why hyperactivity was not present in all forms of brain damage and brain dysfunction?

They were forced to take a closer look at the problems and deficits that children with ‘Minimal Brain Damage’ Symptoms were having instead of focusing on a problem in the brain that could not be observed or defined.

The idea of ‘Minimal Brain Dysfunction’ was later replaced by many specific disorders such as. . .

- Hyperactivity

- Learning disability

- Dyslexia

- Language disorders

(Barkley 2006a; Rothenberger and Neumärker 2005).

In 1968 in the official diagnostic nomenclature, i.e. the second edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-II) (Barkley 2006a; Volkmar 2003) the concept of a diagnosis of hyperactivity was added ”Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood”

The Diagnosis of ‘Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood’ was defined with these characteristics.

- Overactivity

- Restlessness

- Distractibility

- Short attention span

This condition was thought to affect young children (Both boys and girls) and it was believed that the behavior would most likely diminish by adolescence. (American Psychiatric Association 1968, p. 50, cited by Barkley 2006a, p. 9).

Attention deficit disorder: with and without hyperactivity (Douglas 1972)

In the 1970’s the idea of children having an attention deficit received more focus than the symptoms of hyperactivity. You could say the concept of ADD (Today called ADHD predominately inattentive) was born.

Douglas wrote a paper for the Canadian Psychological Association where he made a convincing argument for why impulse control and deficits in the ability to sustain attention were more important symptoms than Hyperactivity in the ‘Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood’ disorder.

(cited by Barkley 2006a; Douglas 1984 (1972); Rothenberger and Neumärker 2005)

Douglas also noted that inattention and uncontrolled impulses were the symptoms they were seeing the most improvement on when using the stimulant treatment.

(Douglas 1972, cited by Rothenberger and Neumärker 2005)

His paper completely changed how we viewed the disorder of ADHD. He inspired more research and in 1980 he finally saw the importance of the deficit of attention recognized and a new name was adopted. It would no longer be known as the Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood, but as Attention Deficit Disorder (With or without hyperactivity) or (ADD).

The Attention Deficit Disorder could now be categorized in two types

- ADD – Hyper

- ADD – without hyperactivity

The Symptoms for establishing a diagnosis also changed. It was no longer considered necessary for children to be hyperactive to receive a diagnosis, according to the third edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-III

(Conners 2000).

The new definition of ADD now differed from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) classic definition in their ”International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9)” W.H.O. continued to consider the presence of hyperactivity as an important indicator of the disorder.

DSM-III developing criteria for diagnosing ADHD published in 1980

What is the DSM?

”DSM contains descriptions, symptoms, and other criteria for diagnosing mental disorders. It provides a common language for clinicians to communicate about their patients and establishes consistent and reliable diagnoses that can be used in the research of mental disorders.”

DSM-5 FAQ – American Psychiatric Association

”Work began on DSM–III in 1974, with publication in 1980. DSM–III introduced a number of important innovations, including explicit diagnostic criteria, a multiaxial diagnostic assessment system, and an approach that attempted to be neutral with respect to the causes of mental disorders.”

DSM History – American Psychiatric Association

DSM-III went on to develop the criteria for an ADD diagnosis. “an explicit numerical cutoff score for symptoms, specific guidelines for the age of onset and duration of symptoms, and the requirement of exclusion of other childhood psychiatric conditions”

(Barkley 2006a, pp. 19 f.)

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder 1987 (DSM-III revised to DSM-III-R)

The revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-R) in 1987 was brought on by the lack of agreement surrounding the concept of hyperactivity. At this point, no one knew if the disorders were definitely connected or if they should be considered two separate psychiatric disorders.

The revision of DSM-III to DSM-III-R removed the subtypes and changed the name to ‘Attention deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)’

‘ADD without hyperactivity was removed as a subtype and became a residual category ‘Undifferentiated ADD'(Rothenberger and Neumärker 2005).

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder 1994 (DSM-III-R revised to DSM-IV)

At the end of the 1980s, the research found that children with ADD (without hyperactivity) were different from children with ADHD who displayed hyperactive symptoms.

(Barkley 2006a)

Children with ADD without hyperactivity were seen as. . .

- Daydreamy

- Hypoactive

- Lethargic

- Disabled in academic achievement

- Nonaggressive

- Less likely to be rejected by their peers

(Barkley 2006a, p. 21)

New neuroimaging techniques helped give researchers a better picture of what they were dealing with, and surprisingly the neuroimages supported the historical idea of brain-damage or brain-dysfunction (Barkley 2006a).

ADHD was finally recognized as a chronic disorder that often persisted into adulthood in the 1990s

(Barkley 2006a) (Döpfner et al. 2000)

After a large trial, the possibility of receiving a diagnosis for ADD or a solely inattentive diagnosis was reintroduced, and ADHD was divided up into three subtypes.

(Lahey et al. 1994)

The subtypes were as follows:

- Predominantly inattentive type

- Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type

- Combined type with symptoms of both dimensions

(American Psychiatric Association 1994)

The DSM-IV included examples of problems adults can have in the workplace, when they have ADHD, in the description of symptoms.

(Barkley 2006a)

In 1994 a conference on gender differences in ADHD was held for the first time!

In the USA the first conference on gender differences in ADHD was held in 1994 (E. Arnold 1996).

The point of the conference was to look at how ADHD manifested its self differently in boys/men vs girls/women. Up until this point, ADHD in girls was mostly compared to ADHD in boys, and researchers realized that there was a need for a closer look at how ADHD affected girls.

Girls and women have some issues that are specific to them which needed to be considered in the light of ADHD. How these issues affected recognizing ADHD in girls/women and being able to diagnose ADHD in girls/women was also an interesting topic of discussion.

For instance, some of the questions discussed were. . .

- How do women’s hormones affect ADHD?

- Does motherhood affect ADHD?

- What kinds of ADHD symptoms are present in girls at different ages?

- Should girls/women with ADHD receive the same treatment as boys/men?

- Does comorbidity affect women differently than men? (Comorbidity refers to disorders that often coexist with each other such as anxiety, depression, and ADHD)

- Is ADHD a valid diagnosis for girls/women? Should girls receive another similar diagnosis?

- Should girls have different criteria for getting an ADHD diagnosis than boys?

- Should girls have fewer criteria than boys?

They also discussed if the present way of diagnosing ADHD was effective at detecting girls’ symptoms.

They noted that Even though there were fewer girls with ADHD than boys, ADHD girls still made a sizeable group.

Even though ADHD was one of the most well-studied diagnoses within child and adolescent psychiatry, it was scientifically demonstrated, for the first time (at this conference), that girls had been practically excluded in the comprehensive field of research on ADHD.

PARAPHRASED FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG, Gillberg Neuropsychiatry Centre

The uneven distribution of ADHD among girls and boys was hard to explain this issue provoked much discussion. This conference was influential in the expansion of research on ADHD in girls.

(Source) https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/108705470200500302

(Source) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S089085670961488X

The first meta-analysis on gender differences and ADHD was published, 1997,

1997 marked the first publishing of a meta-analysis on gender differences and ADHD. (M. Gaub & C. Carlson).

This was an article summarizing 16 studies on ADHD. the results showed. . .

- ADHD among girls went undetected by teachers

- Girls with ADHD acted out less than boys with ADHD

- ADHD girls faced more exclusion from peers

- Girls with ADHD seeking care had greater difficulties compared to boys.

(Source) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0890856709626125

In 1998 Girls with ADHD in Sweden (DAMP in Swedish) were looked at as a separate group from boys.

At a conference in Gothenburg Sweden in 1998, Girls with ADHD (called DAMP at the time in Sweden) were addressed as a separate group from boys with ADHD (DAMP). DAMP stands for Deficits in Attention, Motor control, and perception.

This was the first time these groups of children were addressed separately in Sweden.

The ”Girl Project” began in Gothenburg Sweden in 1999

Svenny Kopp and Christopher Gillberg headed up the ‘Girl Project’ in 1999 They examined one hundred girls ages 3-18. All of these Girls sought professional care for concentration problems and/or social difficulties (for example interacting with peers posed a problem) The girls were then examined multi-professionally.

The Girl project received funding from the Swedish Inheritance Fund. The fund is replenished every year by those who neglect to make a will and have no next of kin or obvious heir.

Department of child and adolescent psychiatry (now the GNC) at The Queen Silvia Children’s Hospital in Gothenburg was the hub for this project.

Girls with ADHD were studies in this department since the middle of the 1970s, but the research on girls with ADHD was not equal to research done on boys with ADHD.

This project was revolutionary because it fueled an ‘awakening’ as psychologists and researchers realized the great need for more research focusing on girls with attention deficits and/or autism.

Svenny Kopp wrote a doctoral thesis on Girls with Attention deficits and/or Social deficits (S. Kopp 2010). http://(S. Kopp 2010)

The girls in the girl project were followed up into adulthood. Although there are currently no publications about these girls as adults we hope that follow-up studies will be published in the future.

1999, Joseph Biederman Published a Study on Girls with ADHD

J. Biederman’s study of girls with ADHD was the most important study written on the subject at the time and is still influential today.

144 girls with ADHD were compared to an equally large number of girls without ADHD. This group was then compared to the same number of boys which was also divided up into subgroups of ADHD and non-ADHD peers.

Biderman found evidence that there were no diffenences between the ADHD symptoms of boys and girls and that boys and girls had the same level of the disorder.

(Source) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11772687/

Gillberg Neuropsychiatry Centre

”Understanding Girls with ADHD” by K. Nadeau, E. Littman, P. Quinn published 1999

”Understanding Girls with ADHD: How They Feel and Why They Do What They Do” Book by Ellen Littman, Kathleen G. Nadeau, and Patricia O. Quinn was published in 1999.

“Historically, research on ADHD has focused almost exclusively on hyperactive little boys, and only in the past six or seven years has any research focused on adult ADHD,” says Nadeau. “And the recognition of females (with the disorder) has lagged even further behind.”

K.athleen G. Nadeau

“Girls with untreated ADHD are at risk for chronic low self-esteem, underachievement, anxiety, depression, teen pregnancy, early smoking during middle school and high school,”

Kathleen G. Nadeau

As adults, women with ADHD are at risk for. . .

“divorce, financial crises, single-parenting a child with ADHD, never completing college, underemployment, substance abuse, eating disorders and constant stress due to difficulty in managing the demands of daily life–which overflow into the difficulties of their children, 50 percent of whom are likely to have ADHD as well,”

Kathleen G. Nadeau

“Girls with ADHD remain an enigma–often overlooked, misunderstood, and hotly debated,”

Ellen Littman, PhD.

Ellen Littman, PhD. advocates for a reexamination of how ADHD is defined. She was one of the first researchers in the field of psychology to focus on gender differences in ADHD.

“We can’t make assumptions that what applies to males will apply to females–females have different hormonal influences to start with that can greatly affect their behavior.”

”Females are socialized differently and therefore tend to express themselves in a different manner, and are more susceptible to such problems as depression or anxiety that again influence behavior. This suggests that ADHD ‘will manifest and express itself differently in females”

“But only research can tell us this definitively. Until then, these are assumptions that we make.”

Julia J. Rucklidge, PhD, assistant psychology professor at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand

It’s a fact that many women aren’t diagnosed with ADHD until their late 30s and 40s. . .

“One of the most common pathways to a woman being diagnosed is that one of her children is diagnosed. She begins to educate herself and recognizes traits in herself. These women are (usually) going to be older,”

KATHLEEN G. NADEAU

Women are often older at the time of an ADHD diagnosis because their children are often not diagnosed with ADHD until the middle of elementary school.

(Source) https://www.apa.org/monitor/feb03/adhd

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in 2000, (DSM-IV revised to DSM-IV-TR)

The revisions to DSM-IV were needed to keep the text current, but most of the changes were made in the description of ADHD not in how ADHD was diagnosed, etc. (American Psychiatric Association 2009)

DSM-IV’s field trials did not include adults. The oldest people in the trials we 17 (Lahey et al. 1994), and this called into question the criteria for diagnosing adults since more research was needed to see if Adults needed different criteria for a diagnosis than children or adolescents. (Fischer and Barkley 2007)

Psychologist Stephen P. Hinshaw, published a Study on Girls with ADHD (2002)

Preadolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: I. Background characteristics, comorbidity, cognitive and social functioning, and parenting practices was published by Stephen P Hinshaw.

Girls with all three types of ADHD participated in this study.

Girls with ADHD exhibited dysfunction in the following areas:

- Cognitive performance

- Behaviour (both internal and external)

- Academic performance

- Comorbidities

- Authoritarian parenting caused dysfunction

- Peer status

He found that girls with ADHD predominately inattentive were often more socially isolated than girls with ADHD combined type, but girls with ADHD inattentive were less socially rejected.

Stephen P. Hinshaw

He concluded that more research was needed in specific areas.

(Source) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12362959/

Criteria for diagnosing ADHD DSM-5 (2013)

”DSM contains descriptions, symptoms, and other criteria for diagnosing mental disorders. It provides a common language for clinicians to communicate about their patients and establishes consistent and reliable diagnoses that can be used in the research of mental disorders.”

DSM-5 FAQ – American Psychiatric Association

The DSM-5 (May-18-2013) has redefined some of the criteria for receiving an ADHD diagnosis and defined some of the criteria more thoroughly. Adults and adolescence (17 and older) only need to struggle with five symptoms on each list while children need to have problems with six points on each list.

In other words. . .

Adults need the following to get an ADHD diagnosis

- 5 inattention symptoms

- 5 hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms

- Must meet the extra requirements

Kids need the following in order to get an ADHD diagnosis

- 6 inattention symptoms

- 6 hyperactivity-impulsivity

- Must meet the extra requirements.

The symptoms need to be present for a minimum of 6 months and must be deemed inappropriate for the person’s level of development.

The symptoms fall into two categories of inattention and Hyperactivity-impulsivity

(Source) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3955126/

Hinshaw went on to do more significant reasearch on girls with ADHD

Inattention Symptoms

Children must have six of these symptoms. Adults and adolesence 17 and older only need to have five symptoms.

- The person is careless and therefore makes lots of mistakes at work, in school or in any other activity. They don’t seem to notice the details.

- They can’t seem to keep their attention on the task they are performing. Even play and other activities can fail to hold their attention.

- They often don’t listen when spoken to. Even when spoken to directly they don’t seem to pay attention to what the other person is saying.

- Lacks the ability to finish what they start. Can’t seem to finish projects or homework. Can’t follow through with assignments at work or other instructions. They get sidetracked and lose focus.

- Organization is hard for them. Organizing their work assignments, tasks around the house, or other activities is extremely hard.

- They have an aversion to tasks that require sustained mental effort such as concentrating on projects in school or having to concentrate several hours on a homework assignment.

- They often lose items that are necessary for everyday tasks and activities. They may often lose their keys, sunglasses, purse, school books, tools, school supplies, passwords for their computer, paperwork, or their telephone.

- They get distracted easily and often

- They forget events and appointments and are generally forgetful in their everyday life

Hyperactivity and Impulsivity Symptoms

Children must have six of these symptoms. Adults and adolesence 17 and older only need to have five symptoms.

- They often fidget, plays with hands or feet, picks at fingers, or squirms in their seat when they should be sitting still.

- can’t seem to stay in their seat when staying seated is expected. Often gets up and moves about the room when it’s inappropriate.

- Children (Sometimes adolescence and adults) run around or climb on things or up trees in situations when this behavior is not appropriate. (Adults and adolescents may only have a feeling of being restless.)

- They can have trouble quietly participating in play, leisure activities, or hobbies.

- They are often always on the go and they seem to be driven by a motor.

- Talks all the time

- They often don’t have enough attention to wait for someone to ask them a complete question and they often blurt out the answer without hearing the entire question.

- They can’t seem to wait their turn.

- They often interrupt others’ conversations or intrude on others in a way that is not socially appropriate, or they try to butt into the middle of someone’s game or organized play.

Anyone wanting to get an ADHD diagnosis must also have the following:

- They must have symptoms for inattention or hyperactivity-impulsivity before the age of 12 years. (The age by which symptoms of AHDD must have presented themselves was changed from 7 to 12)

- Symptoms (more than one) must be present in at least two situations. For Example, they have trouble at school (or work) and at their extracurricular activities (or hobbies). Example two, trouble with relationships and friends is pervasive and they have trouble with attention at home. It could be any combination of different settings and often it’s more than two settings that cause problems.

- They must be able to document or show clear evidence that their symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity-impulsiveness reduce their quality of life and interfere with their school work, their job, or other types of social functioning.

- They must exclude other mental disorders.

- Mood disorder

- Anxiety disorder

- Dissociative disorder

- Personality disorder

- The symptoms must not be limited to another disorder such as the course of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder. The Symptoms of ADHD must be present when a person does not have a bought of schizophrenia etc.

Paraphrased from DSM-5

(Source) https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/psychology/hyperkinetic-reaction-of-childhood

We have come a long way from the days of denying that Girls could suffer from ADHD, but we need teachers and parents to be better informed about the specific symptoms that are specific to girls so that we can catch girls with ADHD before they suffer from low self-esteem, social ostracization, and potentially harm themselves, or commit suicide!

Annie Eklöv

Check out our Posts on ADHD and our favorite Resources for ADHD before you go!

Below I cite my sources

(Sources) https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1058.9683&rep=rep1&type=pdf https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16482683/

(Source) Crichton A (1798) An inquiry into the nature and origin of mental derangement: comprehending a concise system of the physiology and pathology of the human mind and a history of the passions and their effects. Cadell T Jr, Davies W, London [Reprint: Crichton A (2008) An inquiry into the nature and origin of mental derangement. On attention and its diseases. J Atten Disord 12:200–204]

(Source) Barkley RA. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Guilford, New York: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment; 2006.

(Source) Sir George Frederick Still (1868-1941).Farrow SJRheumatology (Oxford). 2006 Jun; 45(6):777-8.

(Source) Conners CK. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: historical development and overview. J Atten Disord. 2000;3:173–191. doi: 10.1177/108705470000300401.

(Source) On a Form of Chronic Joint Disease in Children.Still GFMed Chir Trans. 1897; 80():47-60.9.

(Source) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20896907/

(Source) Palmer E, Finger S. An early description of ADHD (Inattentive Subtype): Dr Alexander Crichton and `Mental Restlessness’ (1798) Child Psychol Psychiatry Rev. 2001;6:66–73.

(Source) https://docplayer.se/4325867-Flickor-med-adhd-anna-hogfeldt-leg-psykolog-adhd-center-2013-08-22.html

(Source) Conners CK. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: historical development and overview. J Atten Disord. 2000;3:173–191. doi: 10.1177/108705470000300401.

(Source) Rothenberger A, Neumärker KJ. Wissenschaftsgeschichte der ADHS. Steinkopff, Darmstadt: Kramer-Pollnow im Spiegel der Zeit; 2005.

(Source) Rafalovich A. The conceptual history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: idiocy, imbecility, encephalitis and the child deviant, 1877–1929. Deviant Behav. 2001;22:93–115. doi: 10.1080/016396201750065009

(Source) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14570817/

(Source) Bradley C. The behavior of children receiving benzedrine. Am J Psychiatry. 1937;94:577–585.

(Source) https://docksci.com/hyperactivity-syndrome_5aee4b2dd64ab21b46e32a3d.html

(Source) Rothenberger A, Neumärker KJ. Wissenschaftsgeschichte der ADHS. Steinkopff, Darmstadt: Kramer-Pollnow im Spiegel der Zeit; 2005.

(source) Methylphenidate Abuse and Psychiatric Side Effects.Morton WA, Stockton GGPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2000 Oct; 2(5):159-164

(Source) Methylphenidate: a review of its neuropharmacological, neuropsychological and adverse clinical effects.Leonard BE, McCartan D, White J, King DJHum Psychopharmacol. 2004 Apr; 19(3):151-80.

(Source) Ross DM, Ross SA. Hyperactivity: research, theory and action. New York: Wiley; 1976.

(Source) Kessler JW. History of minimal brain dysfunctions. In: Rie HE, Rie ED, editors. Handbook of minimal brain dysfunctions: a critical view. New York: Wiley; 1980

(Source) Barkley RA. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Guilford, New York: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment; 2006.

(Source) Changing perspectives on ADHD.Volkmar FRAm J Psychiatry. 2003 Jun; 160(6):1025-7.

(Source) Conners CK. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: historical development and overview. J Atten Disord. 2000;3:173–191. doi: 10.1177/108705470000300401

(Source) Barkley RA. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Guilford, New York: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment; 2006.

(Source) Fischer M, Barkley RA. The persistence of ADHD into adulthood: (once again) it depends on whom you ask. ADHD Rep. 2007;15:7–16. doi: 10.1521/adhd.2007.15.4.7.

(Source) DSM-IV field trials for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents.Lahey BB, Applegate B, McBurnett K, Biederman J, Greenhill L, Hynd GW, Barkley RA, Newcorn J, Jensen P, Richters JAm J Psychiatry. 1994 Nov; 151(11):1673-85.

(Source) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11772687/

(Source) https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2009-04078-002.html

(Source) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12362959/

(Source) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3955126/

(Source) DSM-5 FAQ – American Psychiatric Association

(Source) http://(S. Kopp 2010)